Precision calibration of digital light projectors using the Moiré effect - How to unveil the unseen...

By Stefan Geissbühler

June 23, 2025 • 6min read

The Moiré effect - an unwanted artefact? In this article I show how we can draw a profit from it and share some insights on designing measurement and alignment tools for high-resolution light projectors with lower-resolution detection equipment.

The manufacturing, alignment, calibration and quality assessment of digital light projectors - i.e. beamers, light engines for 3d printers, 3d scanners or lithography machines and AR/VR projectors - involves an elaborate optical performance characterization. That includes the measurement of geometrical distortion, intensity distribution, sharpness or modulation contrast at different (high) spatial frequencies and field points as well as low frequency regional contrasts.

One of the main difficulties for designing an appropriate measurement system is often the coverage of the eventually large projection field with sufficiently high resolution while providing real-time feedback for alignment. Especially the determination of the projector pixel sharpness throughout the projected area requires a significantly finer resolving measurement system. To this end, ideally an image sensor is placed directly in the projector plane that is to be investigated. Alternatively, a finely grained diffuser screen may be placed and observed with a camera or microscope from a distance. In any case, it must be assured that the resolving power of the measurement system significantly overtops the projector resolution to minimize the influence of the measurement equipment itself on the assessment of projection sharpness. However, often the projector and the measurement image sensor have similar pixel numbers. Consequently, the field-of-view of the image sensor is much smaller than the projection field. To cover the complete projection area, the measurement system must then be scanned over the field, which is usually inappropriate for real-time assessment and in certain circumstances the space requirements for the mechanical scan axes may not even be available.

In order to overcome the limitations in resolving power of the measurement system, I was inspired by a super-resolution optical microscopy technique, called structured illumination microscopy. In this method a high spatial frequency illumination pattern is used to provoke a frequency interference between the fine object structures of the observed sample and the illumination pattern. This so-called Moiré effect transfers the high-frequency object structures that were originally unresolved by the microscope system to lower spatial frequencies that then can be resolved and digitally transferred back to the original fine object structures in an image reconstruction process. That way, the structured illumination microscope can surpass the optical resolution limit of the conventional microscope. In a similar manner, the Moiré effect may be used to overcome the resolution issue when characterizing a light projector…

The Moiré effect is a modulated pattern that results upon superposition of two periodic patterns, such as grids, with different frequencies, phases, and orientations. Often the Moiré effect leads to unwanted artifacts. Well known is the unpleasant effect, when patterned objects such as textiles or regular wall structures are rendered on a digital display or camera:

Simulated image of a patterned textile that interferes with the sampling grid of an image sensor: The image to the left illustrates the effect of a lacking anti-aliasing filter and the image to the right shows the corresponding image with anti-aliasing filter

Digital cameras or displays thus come with either a physical low-pass filter (anti-aliasing filter) installed or perform low-pass filtering in software to reduce that effect. Similarly, in audio applications anti-aliasing filters are introduced to limit the audio frequencies to the Nyquist passband and prevent the development of distracting beating artifacts. On the other hand, as the example from super-resolution microscopy shows, the highly sensitive Moiré effect can also be used in a good cause. For the precise measurement and alignment of light projectors, we can take advantage of the Moiré effect too.

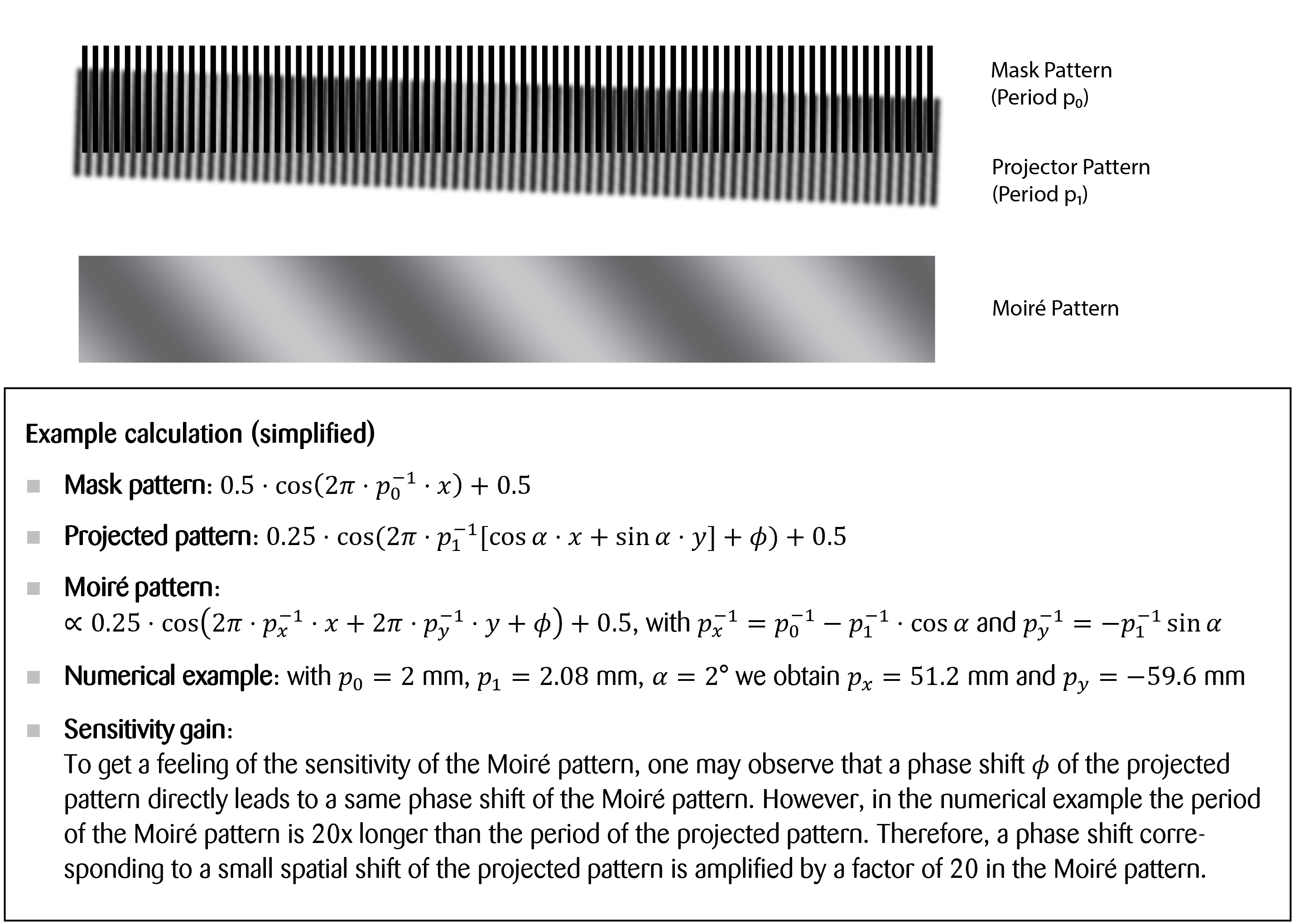

Let us dive into the details of a 1D Moiré pattern and see how we can use it for the alignment and calibration of light projectors:

The Moiré pattern contains a multitude of information on the underlying grid patterns. Assuming a known reference pattern (named mask in the following) with a given frequency, phase, orientation and contrast, the Moiré pattern completely characterises the pattern projected by the device under test. The Moiré contrast, the Moiré period, the Moiré phase, and the Moiré orientation can then be translated into the modulation contrast (which is a measure for the visual acuity or sharpness), the precise location and orientation as well as the size or period of the projected pattern. When the mask and the projector patterns have similar periods, the period of the Moiré pattern (which is given by the inverse of the frequency difference) is significantly longer and can thus be observed with lower resolving measurement equipment.

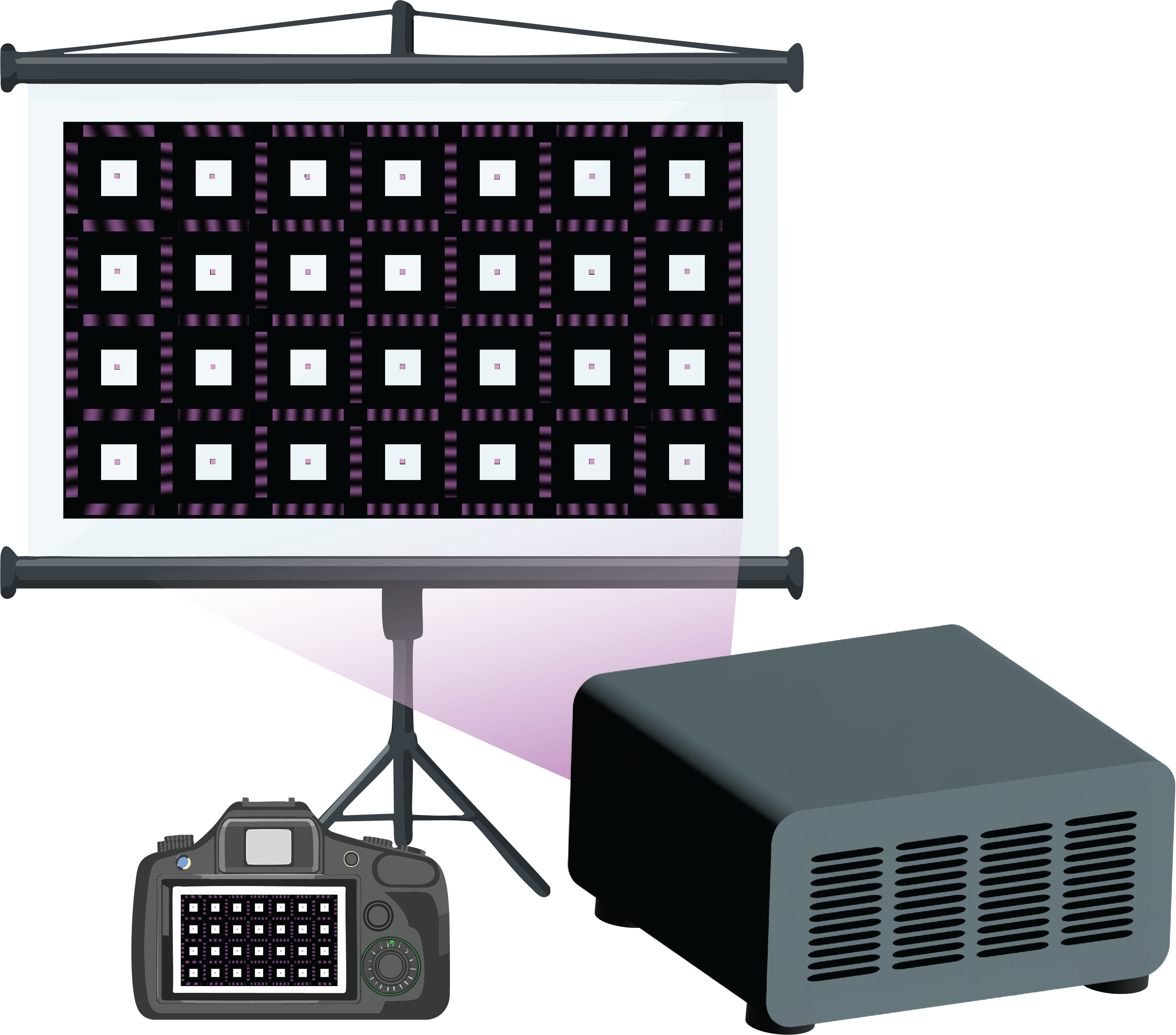

A mask may consist of a transparent plate or glass printed/coated with several absorbing grid patterns of specific frequencies, orientations, and phases. It could also be an absorbing metallic plate with cut out grid structures. A diffuser screen may then be placed behind the mask to observe the resulting Moiré pattern from a distance. Also, a directly printed paper or diffuser sheet/plate can do the job, if the precision of the printed structures and the grain size of the diffuser are significantly finer than the projector pixel. Only the mask with diffuser needs to be placed exactly at the plane of examination from the projector, which is usually easier to accomplish than placing an image sensor there.

The remote observation and the lowered requirements on resolving power may then even allow for complete observation of the projection field with a single camera shot without scanning and can thus also provide a live view for full-field alignment.

This illustrates, how the sometimes unwanted but highly sensitive Moiré effect can also be used to our advantage and may help to unveil the unseen…