Context-Driven Smells

By Phill Royle

April 28, 2025 • 30min read

The Context

I once worked at a scale-up tech firm $company. It had rapidly built its core product suites, gone to market, and attracted serious investment. The next phase was to add the bells and whistles promised to customers, improve quality, and to explore moves into other industry domains. In the UK were two strong product teams, comprising developers, permanent QA and Product members. A separate DevOps team1 prioritised platform work, dropped into teams.

Due to the nature of the customers’ work, the offering was expected to work transparently and without fault. Customers were not interested in working with product teams and instead liaised purely through the strong and motivated sales/Customer Success team2. This meant that bespoke, single-client requests were promised by sales, with little care for priority, complexity, or roadmap, and an adversarial relationship between sales and product teams developed.

The Tech

As is common with start-ups, code was written very quickly in an effort to get to market, broadly following a microservices architecture. It used a mixture of NodeJS and java codebases, with Postgres. Some odd design decisions – using a common staging DB to communicate between microservices rather than queues, codebases that no-one left at $company understood – were problematic, but the real issues were down to quality safeguards. Almost zero tests3, observability, or resilience engineering meant that the team were always surprised by bugs, downtime was frequent and long, and investigations were invariably complex4.

Additionally, $company relied on multiple integrations with 3rd parties, some with well-defined support agreements, and other casual. Changing APIs and other contracts with these necessitated frequent changes of approach, and failures in these 3rd parties were often not detected without customer reports5.

The Bombshell

One of the 3rd party integrations significantly changed its architecture5. We were able to use a pilot of the new version to test our existing product against, and the result was… nothing.

Complete failure.

There was no SLA or formal agreement with the 3rd party, and we had no idea of when the switch from current to new devastating version would take place.

To preserve the anonymity of $company, imagine your business relied on collecting flight information from BA using their public API, and suddenly, they started doing hovercrafts too, upgraded the authentication from a simple token to a double ratchet mechanism, and entirely changed the handshake and payload. And you couldn’t miss a single flight update.

So, our biggest product had to be re-written from scratch with no idea of the deadline, while keeping the current version running at 100% of our customers’ SLAs4.

The team stopped developing new features. They fixed only the most pressing of bugs on the old system, and began rapid prototyping, research, and building of a new application. This time, we would do it right.

We paired, designed for scalability, observability, and recovery, practised TDD, and made great progress. As distractions poured in from the ‘legacy’ version however, the spectre of the unknowable deadline loomed closer, and a core library broke our tests. We made the conscious decision to comment the tests out, and promised ourselves that we would add them in as soon as we had time6. Auto-scaling our Kubernetes cluster could go on the To Do tech debt list too, and we configured a cluster that was over-sized, that we could manually reduce with user data and our shiny new dashboards. Automatic recovery was vital in case we missed any of those ‘BA flight’ events, but time was of the essence, so we hand cranked a ‘simple’ mechanism to manage it.

We crossed the line, and delivered before our deadline, customers and the business were delighted, but our lack of quality had allowed bugs to creep in. We wasted weeks more debugging the ‘simple’ fixes, introducing the same bug over and again, continually flexing the cluster, and spamming users. The customers’ happiness and confidence soon faded, as the team worked relentlessly to build stability, becoming more burned out.

The New Opportunity

Once the new app was finished, rolled out, and stable, the team relaxed, and began thinking about addressing all the tech debt that had built up. This felt like a chore, but also something that we could get behind with pride to regain the quality of the service we had built. Then one of the sales team landed an enormous deal. It would increase our customer base by a factor of 10.

Our new service would scale beautifully. We ran load tests and were delighted.

The rest of the ingestion pipeline though was far from ready – performance bottlenecks, recursive retries from failures overwhelming DBs, ability to scale vertically only was not sufficient7 - and there were myriad other new things to focus on, from onboarding that many new people, to cost optimisations.

The tech debt would have to wait.

Seven Critical Software Development Smells

The points below are identified from the above context. As with code smells (or code-smells.com), there may be nothing wrong here, but experience tells us that it’s worth taking a look.

Smell 1: Siloed DevOps Teams

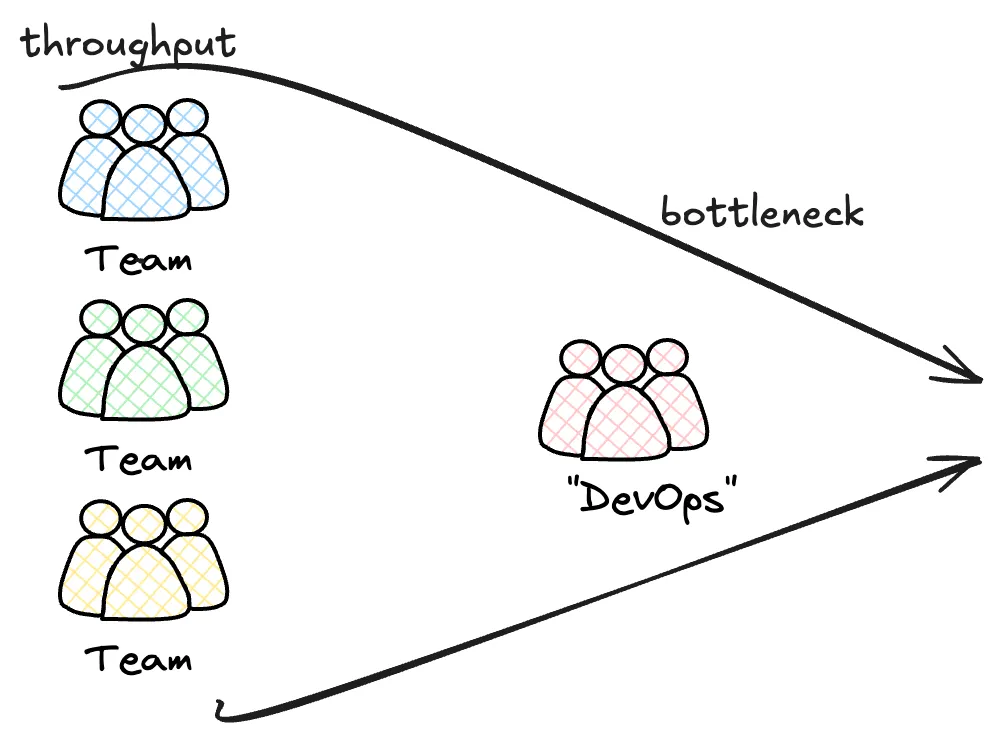

It is very common to see a DevOps or Platform team exist separately from product or feature development teams. There are often cross-cutting, enabling pieces of work that need to be done outside of those teams, so it makes sense, right?

Possibly, but it still smells.

Over separate projects, with separate platform teams, I’ve experienced

- Locked down cloud environment, meaning the creation of a new repo, permissions for services, even monitoring of existing infrastructure is off limits

- No access to IaC, meaning initial requirements, refactoring, even environment variables are passed off to other teams, causing mistakes, bottlenecks, and a batching of requests

- Lack of ownership, and barrier to entry, encourages a blame culture

- The bottlenecks mean that delivery & Time To Value (TTV) are dramatically slowed, and that dev teams and DevOps teams are peppered with distractions

Diagnosis

DevOps isn’t a separate team or magical solution – it’s a cultural transformation that puts collaboration and continuous improvement at the heart of software delivery. The old model of throwing code over the wall between developers and operations is dead.

Each team in an agile organisation should have autonomy and ownership over the products it builds. If part of a team’s responsibility is delegated to a separate team, they lose that ownership, and consequently, dependencies, siloes, conflicts, and blockers emerge. A terrific book to read on this is Accelerate, by Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim. It would have helped $company focus on observability, resilience, and getting that auto-scaling done right.

Here’s how to make DevOps work:

Short-term wins

- Embed DevOps engineers into the team, and help them to shift left. It can be challenging to re-organise teams. Perhaps initially a nominated DevOps engineer simply attends standups, planning, kick-offs, and retros, offering expertise earlier, and becoming more aware of the team’s expectations; later, pairing with devs, working together to improve processes and tools. It can be challenging for that person to prioritise work for the team and their DevOps chapter, so try to make workloads as visible as possible.

- Create shared tooling that reduces friction and standardizes best practices, while still allowing teams autonomy

- Implement cross-team knowledge sharing and collaborative problem-solving

- Invest in automation that speeds up deployment and reduces manual work, for example CICD pipelines. Big bang deployments are bad! Automate moving away from them

Long-term transformation

- Build a culture of psychological safety where teams are trusted to experiment and learn

- Encourage teams to own their entire service lifecycle, from design to production support. Not only does this improve software TTV and quality by removing blockers, it empowers teams, and makes retention better

- Invest in continuous learning and skill development across engineering teams

The goal isn’t perfect infrastructure – it’s creating an adaptive, resilient environment where teams can move fast, learn quickly, and deliver value consistently. DevOps isn’t a destination; it’s a continuous journey of improvement.

It makes sense that there is still a community pushing in the same direction and seeing the full picture though. Likely there should be a common infrastructural strategy within an organisation. Its purpose though should be to encourage congregation around set patterns, and to provide tools to enable that and make teams’ likes easier. A DevOps engineer should influence the culture of the organisation, educating and enabling people around them, making others champions of the cause. It should not be concerned with guarding the terraform files, holding the keys to IAM so that all new repos go through them.

One of the best experiences I’ve had involved teams being given really comprehensive training, a safe culture of not being afraid to break things in test, and full stack ownership. Each dev was given full IAM permission, but little else. If I needed to do something, I could give myself the permission to do it – a message was sent out to everyone, and audit trails were kept. Within the next few hours, my permissions would reset to the default. I wasn’t blocked, but neither was I able to go rogue.

Trust your teams. Give them the right tools, support their growth, and watch innovation flourish.

Smell 2: Sales-Driven Feature Prioritization

Even an excellent sales team is likely incentivised by keeping the customer happy, rather than what the customer needs, or what’s best for the product. This leads to conflicting product strategies, and according to the proverb, “if you chase two rabbits, you will not catch either one”.

With new requirements streaming in from all sources, the product backlog grows, customers become frustrated, and soon everything is a high priority feature - “if everything is urgent, nothing is urgent”. The development team begins to rush, tech debt is not included in a sprint, nice-to-haves are missed, and soon quality suffers.

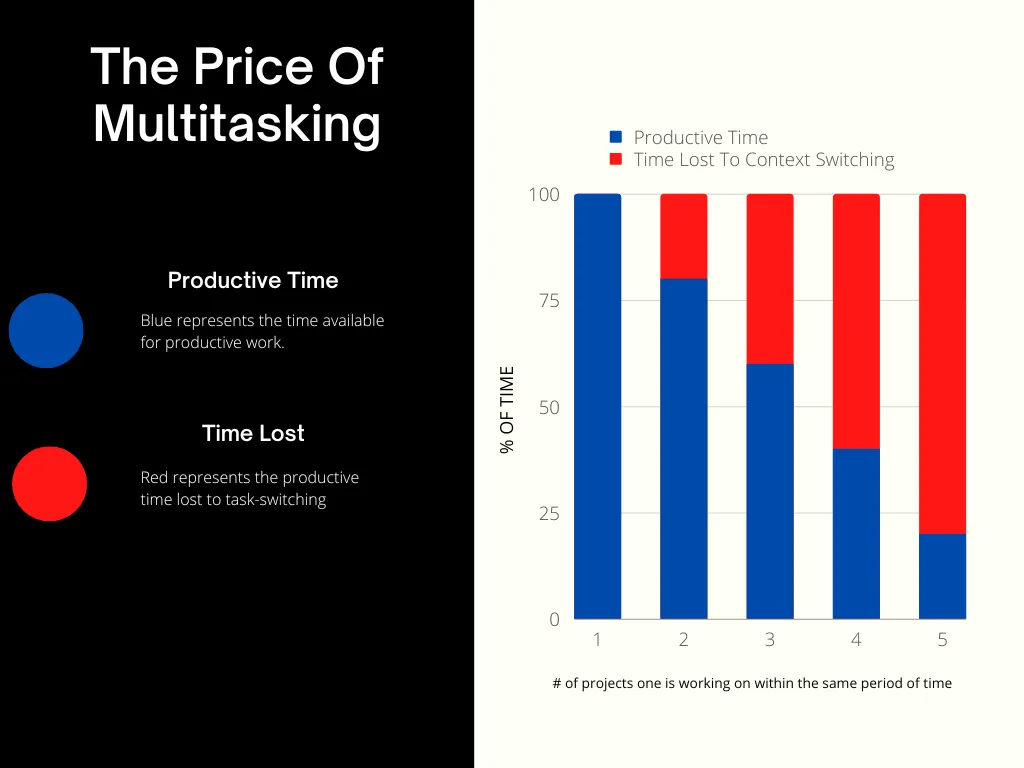

When new tasks drop to the team, members are forced to context switch between new and old pieces of work. Scrum.org says this can lead to a 20% productivity hit, and that this increases linearly with additional tasks.

Even something as simple as answering emails can pull you out of your flow state and it can take 20 minutes or so to get back to focus. Not only will this make work progress more slowly, it increases error rates and leads to a reduction in developer engagement.

Further, the Sprint goals (or prioritised backlog, or whichever framework you use) are the most important pieces of work that bring the most value right now. By diluting your focus, you increase the Time To Value of that product work, pushing out deadlines, sacrificing quality, losing fast feedback, and missing out on all that lovely revenue you could be earning.

Without real access to customers, the Product Team are shooting in the dark, even with decades of domain expertise. The market changes, different customers have different needs, maybe Clippy doesn’t solve our users’ needs. The best engineered, most thought out product in the world will fail if it doesn’t do what people need it to do.

Not only are we building poorly, we’re not even building the right thing.

Diagnoses

Protect your backlog, and your team

- Have very tight controls on what can come into a Sprint (or whatever). Unless it’s a crucial defect, think very hard about whether it should wait a few weeks.

- Implement Work In Progress (WIP) Limits. Our goal as product teams should not be to individually get the most amount of work done, it should be to deliver the most amount of value as quickly as sustainably possible. WIP Limits reduce the amount of active work in the in the team at any given time, which not only speeds up the delivery of that value, it reduces the amount of work ‘nearly’ done, makes delivery more predictable, reduces context switching, and introduces ‘slack’ time, in which the team can recuperate, tackle tech debt, refactor that niggly test. Some excellent resources include The Ship Building Simulation and The Kanban Flow Simulation.

Kent Beck wrote an inciteful post based on Beth Andres-Beck’s Forest & Desert concept. In it he talks about having ‘no’ bugs, not because of a No Bugs policy, but as a result of the team owning planning, design, testing, and collaboration. Both posts are worth a read, and it becomes obvious that $company were in the desert – on moving out of the desert “No developer can do it alone, and no amount of technology will get us there, but it is possible”, which leads to:

Move to a Product-Centric Model

Having the sales team, good as they are, be the only customer contact means that as well as the scattergun prioritisation above, you miss out on a lot of things:

- Requirements for your product pass through an extra layer before they get to the product team. Chances of missing details are dramatically increased, but you also miss out on being able to question those requirements directly. Why do you want this? What are you hoping to achieve? It removes that chance of being able to examine their real problem and find a better solution.

- The Product Team should be the people in charge of the long-term strategic direction of the product. It’s so easy for the sales team to miss some nuance in this, and the strategy begins to splinter and fray, and before you know it, you’re building bespoke systems for each customer.

- The whole point of agile delivery is making small pieces of value quickly and then seeing whether it works for the customer. For that to work, you need a good, trusted, direct means of communication with that customer. Having sales in the way jeopardises that fast feedback and means that a culture of experimentation can never get off the ground.

I highly recommend reading Transformed, by Marty Cagan, which discusses all of this, prescribing a strong partnership with the sales team, rather than an adversarial one. It goes on to push for Product-Centric teams, rather than project- or feature-led ones. In this world, the Product Team steers the direction of a product, know the domain, know the customers, and can be more innovative and move faster. This transformation can be difficult to get right - Zühlke has expertise here and can readily provide advice.

Smell 3: Absence of Testing

This smell should be the most obvious. In this case, the lack of tests across the ‘legacy’ suite of services meant that when bugs appeared, it was difficult to narrow down the cause of the crime, so that investigations often took days instead of minutes.

Worse than that, often a fix to solve one bug would cause issues in other places that could go undetected – sometimes even previously fixed bugs would resurface. Any deployment would take at least a day longer than it had to because of the massive manual test regression that had to be run, and scheduling that around the demoralised test team caused further delays.

While not a silver bullet, TDD would almost certainly have helped to make the code structure better, and to reduce the dependencies that crept in.

Diagnosis

It can be faster to build software without tests, it’s extra code to write, extra thinking time, sometimes the abstractions can be hard, and why the hell is the timestamp always wrong.

But, what happens in 2 weeks, or 2 months, when you can’t remember how this worked, or need to add a new feature and have no idea if it’ll break that thing over there? What if the shiny calculator app works beautifully, unless the user enters an odd number, or that profanity filter stops you using any words that begin with ‘f’?

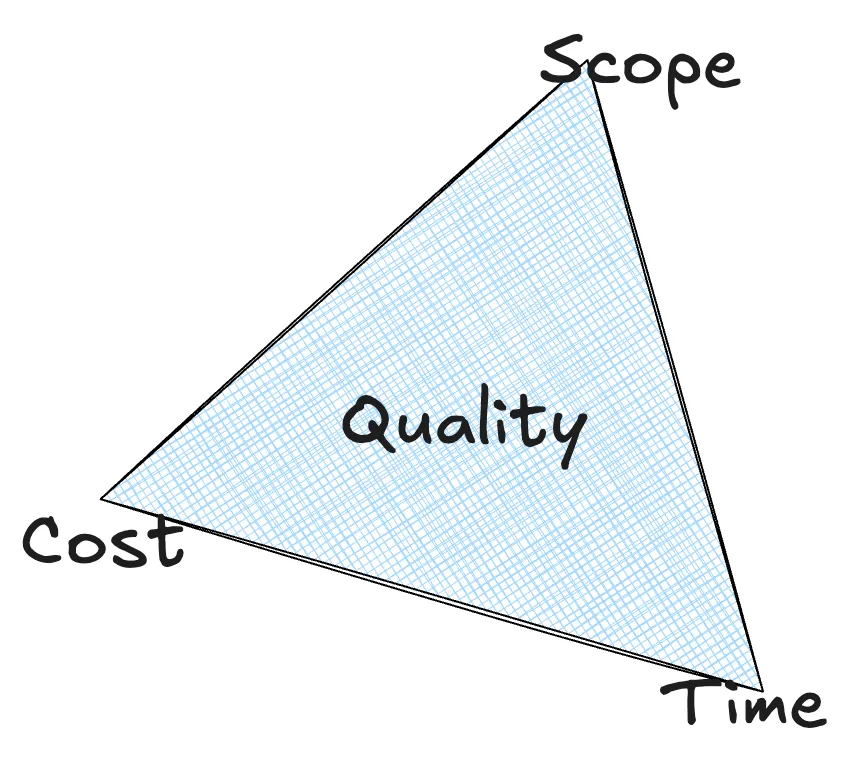

Your code may be built more quickly, but you have sacrificed its quality (see The Iron Triangle) and as we know, we’re actually aiming to deliver value, not bits of code.

In fact, TDD can speed up development. It helps you to focus on what’s actually required (KISS), prevents you from building a Porsche when a van is what you need (YAGNI), and by biting off small chunks of the problem as tests, and iterating on them, you can make an enormous task smaller.

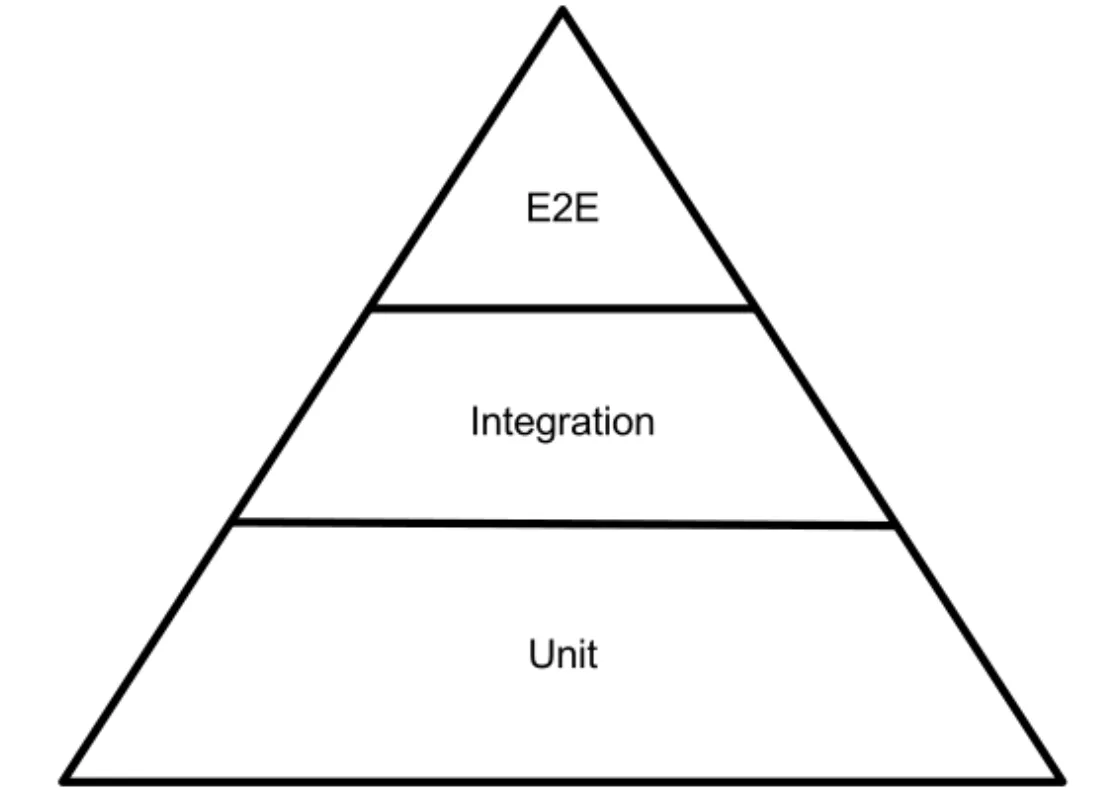

- Pay close attention to the Test Pyramid, check if you’re getting it wrong – structure your tests appropriately. Focus on many small, fast, low-level tests, fewer wide integration tests, and a very limited number of complex, slow, end to end tests. You want to aim for the situation where you’re completely confident that your code does what it should, but without being brittle, taking an age to re-write, or taking an age to run. Running a test suite is the very first piece of fast feedback your code gets, so make sure it’s fast.

- Keep abstraction in mind. Adding a field or two in an object should not mean days of test refactoring.

- An introduction to unit testing

- Getting started can be daunting, especially when you’re starting from near zero – getting a good level of test coverage would take weeks on a large project. Typically, it’s recommended to ensure a good level (80%?) of test coverage on each new commit to the codebase, that way you ensure that your new stuff is of high quality, you begin to make inroads slowly, and gradually coverage improves. There are many tools to measure that, but a very good all-rounder is SonarQube which allows you to define quality gateways whereby commits can’t be merged without that test coverage

- Every time you fix a bug, ensure its covered by your test cases

- Make sure to pay attention to the quality of your tests as much as you would the code itself. Once, when trying to understand a large legacy system we had inherited, my pair and I commented out every line of code. When we ran the test suite, only a single test failed. I have never seen mutation testing used in real projects, but I’m fascinated by mutation testing.

- Make sure to collaborate with your test team around test coverage (and, well, with everything). You should find that with better test coverage and automated pipelines, those day long manual regression tests can be dispensed with, helping you to release more safely and more often

Smell 4: Being surprised by bugs, long downtime, and complex investigations

Surprise incidents are a classic sign of poor observability. Think of observability as your application’s vital signs – without good monitoring, logging, and tracing, you’re essentially working in the dark. You can’t fix what you can’t see. This was compounded by the lack of testing, making the system more opaque and brittle.

Those long, frequent outages are screaming “resilience problems!” A resilient system bounces back from failures. It handles errors gracefully, routes around problems, and keeps running even when things go wrong. But building this resilience requires careful design and the right patterns – circuit breakers, fallbacks, and automated recovery.

When your team spends hours unravelling each issue, that’s often the result of these two problems feeding each other. Poor visibility makes it hard to build robust systems, while fragile systems create more incidents that are harder to debug.

While writing the new application, the old one had to be kept at 100% SLA – we knew what this meant, “keep the lights on”, but when you can’t measure performance or errors, how can you be sure of this? It falls back to a gut feel and to context switching to urgent bugs and data reconciliation.

Diagnoses

Logging

Add logging to your applications so that you can see what they’re doing. Aggregate the logs into something like the Elastic Stack so that all of your logs from all of your applications, are visible from one place.

- Structure your logs to make them more searchable, and to give you the information that you will need in an emergency. JSON is common.

- If a user journey spans many services or stages, you might want to be able to stitch each of those logs together into a coherent story, so think about adding a journey-specific correlationId to logs that can be filtered for.

- Take great care not to include PII in logs, you could be vulnerable to information leakage. You can control this with different log levels for different environments, and by masking fields as they’re written.

- Log volume can grow very quickly and can add up to significant costs.

Think about what retention period is useful, perhaps only log

errorlevel and above in production, refine what’s needed after it’s been developed. - Try to enforce the correct level of log throughout your codebase according to something like this.

tracelevel is useful in development environments, but in production would be far too noisy. - At $company there were many logs. So many error logs that it was impossible to see what was cause for concern, what was mis-labelled, and what was a bug from 4 years ago that no-one cares about. Logs, like anything else, must provide value.

Observability

Build dashboards so that you can see what’s happening, now and over time, Grafana is a common tool for this, simple to use, with tons of data ingestion sources. It allows you to ingest metrics from your application, and to build charts, dashboards, and alerts from them. Start slowly and gradually build up more and more insightful views. It’s common to start with simple things like http statuses, memory stats, error logs, etc.

Define realistic thresholds and add alerts so you’re aware when they’re crossed. You don’t want to spam the team with false alarms, but likewise you don’t want to miss bad events. Tweak them often.

With a little more visibility over what’s happening inside your codebase, use those metrics to help you prioritise – and measure – improvements to it. If a particular operation is taking much longer than others, try to refactor it; if you get higher than normal error rates for a given API, investigate

Smell 5: Undetectable failures in 3rd party services

Silent failures are like invisible leaks in your plumbing – they can cause serious damage before you even notice them. When third-party APIs degrade gracefully or fail subtly, your application might keep running while quietly delivering bad data or poor performance. Worse is that your customers are exposed to your dirty laundry, which severely damages the reputation you’ve built.

3rd party APIs may continue to work, but have changed their contract, and that could have implications just as severe on your service as total failure.

In this case, $company had a reliance on a 3rd party with no agreement in place. There was no technical, legal, or even unofficial partnership, it was just a core dependency that $company had no control over.

This is an existential risk to the business.

The consequences of failure here were felt by $company in terms of reputational loss, customers leaving, 6 months of development team focus, and burn out, and had the team not been successful, the consequences could have been the end of the company.

Diagnosis

You obviously don’t want to test your 3rd party dependencies’ code, but you should test your interaction points with them.

- Defensive programming can help – assuming any interaction is potentially incorrect or missing. Build comprehensive testing to be confident of managed service degradation. The worst thing a service can do is to give the wrong information.

- Often, 3rd parties provide testing APIs to integrate with, and it’s worth including very simple calls and tests to them in your integration layer – if the API contract changes, your tests will fail.

- Make sure that you have good error handling and alerting around the API, so that when it goes wrong, not only do you handle it gracefully, you know about it.

- Review your code to see how isolated the 3rd party is, try to keep it well contained. If a 3rd party service is consistently causing problems, you may wish to move away from it to a new provider. How easy is that to do within the code? It’s worth looking at how well encapsulated your integrations are, whether code and assumptions are smeared throughout your codebase, or whether you have enough abstractions that you can simply drop in a replacement.

- Keep the version of the 3rd party well controlled – your code plays well with the current version, but perhaps not the next one. When it’s time to update versions – don’t let them get too old or you lose functionality, security, and support – do so in a controlled way, protected by tests.

- Internal dependencies from other teams are hopefully more reliable, but human error, siloes, and complex organisations all make mistakes possible, so be defensive here too. Perhaps consider Contract Testing and/or schema validation.

- Add monitoring, logging, and alerting around these calls, looking for errors and response times so that you’re at least aware of the issue.

It’s also vital that the business understands these risks, so make sure to discuss them clearly. You may need extra time to safeguard the code, or the business may need to add legal cover or other mitigations to reduce the likelihood or damage.

Smell 6: Compromising on Quality Under Pressure

The team did a good job initially, learning from past mistakes and building in quality from the start. The fact that they delivered and that the solution was scalable is testament to that. However, even under extreme time pressure, reducing that quality, consciously or not, is a dangerous mistake.

It feels like you’re moving faster, but you’re actually setting a time bomb. Those “temporary” workarounds? They have a funny way of becoming permanent fixtures.

Here’s the brutal truth: there’s never magically more time later to fix quality issues. That “we’ll clean it up next sprint” promise? It rarely happens. Instead, each shortcut adds to your technical debt, making every future change slower and riskier. It’s like putting purchases on a credit card with sky-high interest rates.

Your customers feel it too. Those workarounds often leak through as inconsistent behaviour, mysterious bugs, or sluggish performance. Each quick fix might solve today’s crisis, but it erodes trust with every new problem it creates.

And let’s bust the biggest myth: that cutting quality saves time. You’re just pushing work downstream – where it’ll cost more to fix and cause more damage along the way. That quick workaround today means hours of debugging next month, frustrated customers, and developers who spend more time fighting fires than building features. Quality isn’t just about perfect code; it’s about maintaining velocity and trust. When you sacrifice it, you’re borrowing time you’ll have to repay with heavy interest.

The Iron Triangle is real. With a fixed time scale, it is far better to reduce scope than sacrifice quality.

Diagnoses

Manage Stakeholder Expectations

This is the crucial part – that pressure is coming from the dev team, but mostly from outside it. Convince them (and you) that quality is non-negotiable. By skipping it, we’re essentially taking out a high-interest loan against our future velocity. Use concrete examples from other parts of the project – all that tech debt, those day-long investigations. You can’t guarantee that your product will be bug free, but spending a little time now will save you 4-5 times that in production.

The Iron Triangle

We know that we can’t speed up development, with fixed scope and money while maintaining quality We had a fixed (unknown) deadline, so maintaining quality would mean flexing on:

-

Extend the team

-

This can help! Extra people can do extra work, but

-

It can also add complexity to communications

-

Onboarding will take longer than you think – will the benefit new people bring cost too much time to achieve?

-

Adding more chefs won’t make water boil faster - beware parallelisation fallacies

If you do bring new people in, ask them to focus on isolated, well-defined areas, that don’t need huge context. Pair with them to get them up to speed more quickly and to maintain team standards.

-

-

Reduce Scope

-

Break features into smaller, must-have increments

-

Identify and postpone nice-to-have features

-

Be clear about trade-offs: “We can deliver these core features with proper quality, or all features with significant risks. Here’s what those risks mean for the business…”

In $company, we introduced “MMVP” – Minimum Minimum Viable Product – the smallest thing we could launch that would work, but that we would never want to give to our users. A smell in itself for sure, but desperate times. If the deadline passed, and our old product was dead, we could limp on with our MMVP, saving the business, but surely not delighting our customers. I still think this was a solid tactical move. The problem was that as soon as we finished the MMVP (without tests), we moved right on to the MVP phase, without pausing to add those tests in.

-

Hold Yourselves to Account

A good dev team is as invested in beating the deadline as anyone else, so even when you have reduced scope, convinced the CEO, and brought in those shiny but costly new devs, it can be oh so tempting to power on and race to the finish line.

Slow down.

Keep it sustainable, make sure your test coverage is good, keep that great code structure, continue to pair and review code. Future you will thank you for it.

Smell 7: Ignoring the Warning Signs

Although the 3rd party service changing didn’t directly impact the second team, it should have served as a wakeup call to significantly address software quality across the organisation. While one team had to stop everything to focus on the problem, the other team carried on as normal, shipping new features dreamed up by customers and adding cherries on top of existing products. What should have been an opportunity for root and branch review was ignored, so when the big new opportunity arrived, there was 6 months of work to do to get ready for it.

Teams should always be looking for and addressing technical debt, and fixing that should be part of the normal development process – stop making things worse, and begin to make it better.

Worse, learnings in the first team were not shared, and the second team faced a similar mountain to climb and could easily have been better prepared.

Accepting the status quo meant that $company very nearly lost out on that transformational deal.

Diagnoses

Scenario-based Questioning

Frequently, and as a team, ask yourself scenario-based questions to find out what would happen with situation x, and mitigate against it. For example, what happens if we’re deployed on AWS and eu-west-1 goes down? Is our service dead? Will it spin back up? Is there a cost or reputational impact? Will it work on a different region? What if that S3 bucket of images is deleted? Do we have a backup? When does our cert expire, do we have a fallback? Look at Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA), practise it as an organisation, and share, and act upon the results.

Address Tech Debt

Technical Debt is inevitable (*contentious), whether consciously added as in $company, or simply due to changes in codebase, newer versions, etc. Some of this can be fixed in the normal day of a dev team, following the Good Scout approach, but larger pieces should be planned into the team’s work.

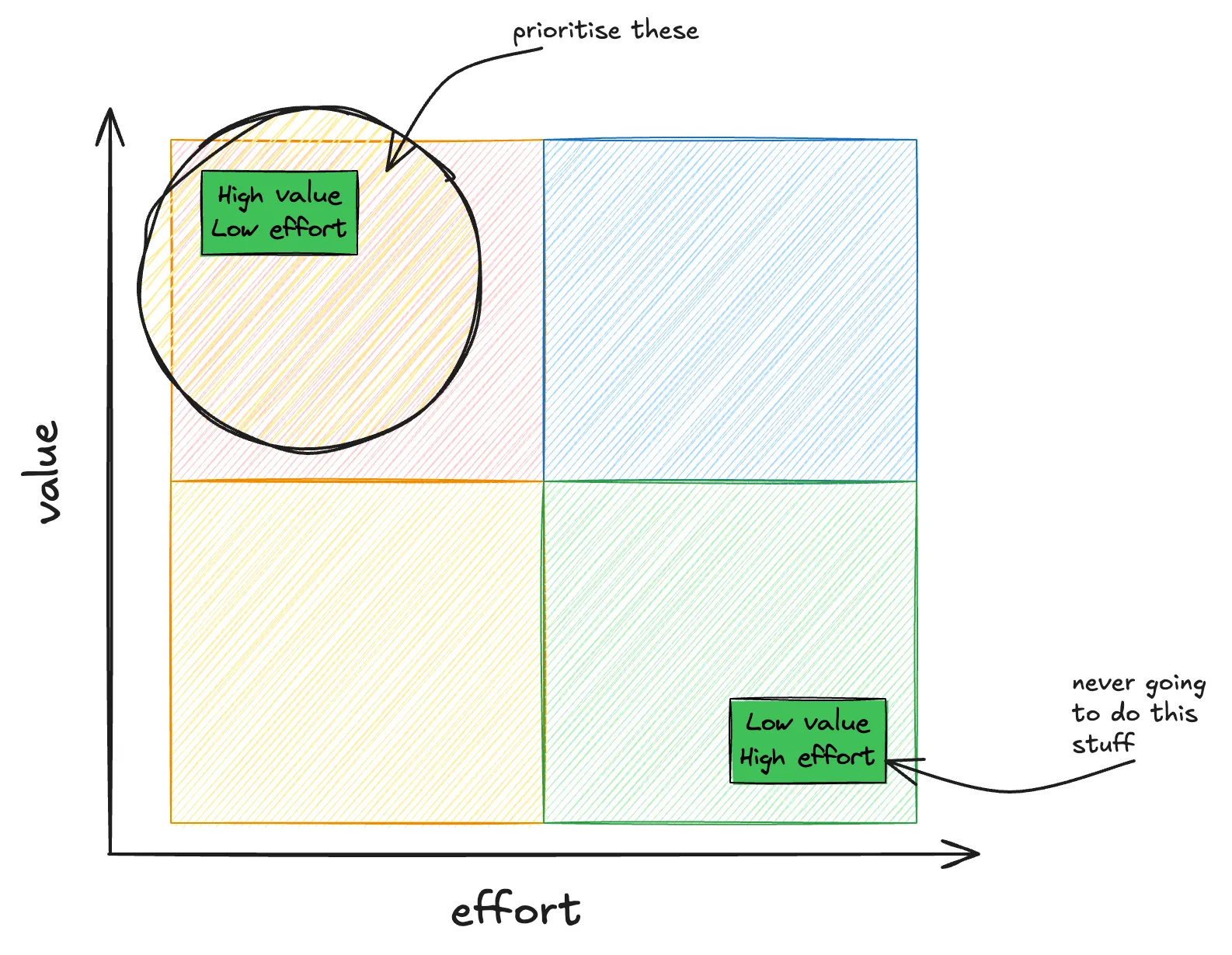

I have found it useful for prioritisation to use an Eisenhower Matrix. As a team, decide whether each piece of tech debt is important or not, complex or not, and prioritise those items that are both simple and important. Some important and complex things need to be fixed, but this approach operates on the 80:20 rule – 20% effort should give you 80% of the value.

Once you have chosen, add them into your backlog as you normally would, and make sure they don’t get deprioritised. The advice for this is that same as for ensuring code quality – and in fact, it’s the same problem!

The identification of tech debt comes in many forms, from many places:

-

Code Signs

-

TODOs from a while ago (or at all)

-

Hard-coded values and magic numbers

-

Over-large functions, or classes that do too much.

Your IDE can help with plugins like complexity checkers, and tools like SonarQube even give metrics on tech debt accrual.

-

-

Operational Flags

- Recurring bugs in a particular area

- Bottlenecks in service x

-

Team Signals

- Devs being anxious about working on a service

- “We really should fix this, but…”

- Knowledge siloes, where only Keith dares to tread

Test Performance

Regular load testing and pen testing are an overhead and expense that often mean they don’t get done. Like house insurance, it’s a cost that you never get value for, until you do. Had $company performed load testing in the 6 months prior to ‘The New Opportunity’, we would have seen the bottlenecks and frailties that the existing codebase had. It still may not have been prioritised in time, but we would at least have known where the effort was needed and what the timescales looked like.

The frequency of these tests will vary according to your business, but should still be regular - a plane is checked after every flight, but your car probably only annually. I have seen load tests performed in an automated pipeline each night, but the costs and set up of that could be prohibitive. Third party pen tests might only be needed twice a year. Ask yourself if you have confidence in your product - what would happen if your user base doubled or tripled, do you know? What would happen if a bedroom hacker targets it, or a nation-state, and does it matter?

Load testing can be done in-house with tools like Gatling, or outsourced to specialist companies. A lot of security testing can also be done in house – tools like SonarQube, Wiz, snyk are all fantastic at protecting you, but sometimes an external kick of the tyres brings up new things.

How to Prove Hypotheses

I said earlier “there are no silver bullets”. Every company, product, and team are different, and every smell can reveal different things, or nothing at all. I have written about things that have helped me in various places, including at $company, and hope that they would work in most.

If you come across a smell in your codebase, team, or processes, don’t ignore it. Trust your… smell-gut. Bring it up with your team in retrospective (please don’t skip those), sprint planning, or even just in pairing sessions.

Experiment

Give it a go for a couple of weeks and see if it makes a difference. WIP Limits take very little time to set up, try pairing on that big, complex thing, and see how it feels. Speak to the team about it though, convince them first, and make sure they’re excited to try it. Some of these suggestions will take longer than two weeks to realise value – in my experience pairing for example has a large hump at the beginning – it can be tiring, awkward, you can feel like you’ll never find your flow-state again – but if you persevere, enhance your pairing skills, it feels more natural, and you should notice quality results. Moving to a product centric approach cannot be done in two weeks either. Instead, you could try to experiment with a single product or team – give them support and autonomy and watch the results. The Transformed book details three stages, so do take it step by step.

Measure

How do you know if something has worked unless you can measure a difference? Keep an eye on how many defects you get a week, or how many times you’re distracted, how many bits of work do you get done a sprint (and their value). Then experiment and see if there’s a difference. Maybe there’s no difference, but you feel more confident in the face of uncertainty. Maybe things got worse – stop doing that thing (or practice it more). This hope is obviously that things get better. Marginal gains are great. Whatever the outcome, share it with other teams – you’re in this together.

Use DORA metrics.

Check the value

For me, this value falls into a few categories:

- Value to the customer

- Get feedback, and measure satisfaction

- Gather usage metrics, use a/b testing

- Measure support tickets and feature requests

- Looked at abandoned features – what did we build that had no use?

- Value to the business

- Cost savings from improvements

- Revenue from new features and products

- Reduced TTV

- Value to the team

- Shorter lead time, cycle time

- Faster release frequency

- Fewer defects

This is what we’re all about. Are we providing more value now than we were before, and can we do better?

Speak to the team, to the business, and the customers.

Get real feedback.